Table of Content:

- Basics: Ethymology and Meaning

- How is the Spine Measured?

- Static Spine vs. Dynamic Arrow Behavior

- Spine Table

Basics: Ethymology and Meaning

The spine… if you want to buy arrows then you will find this word practically everywhere! But not everyone immediately knows what to make of it. The spine is derived from the draw weight and the draw length, and decides the right arrow for me? But how does this work exactly? That’s precisely what we want to take a closer look at today and dive into the world of ‚the spine‘.

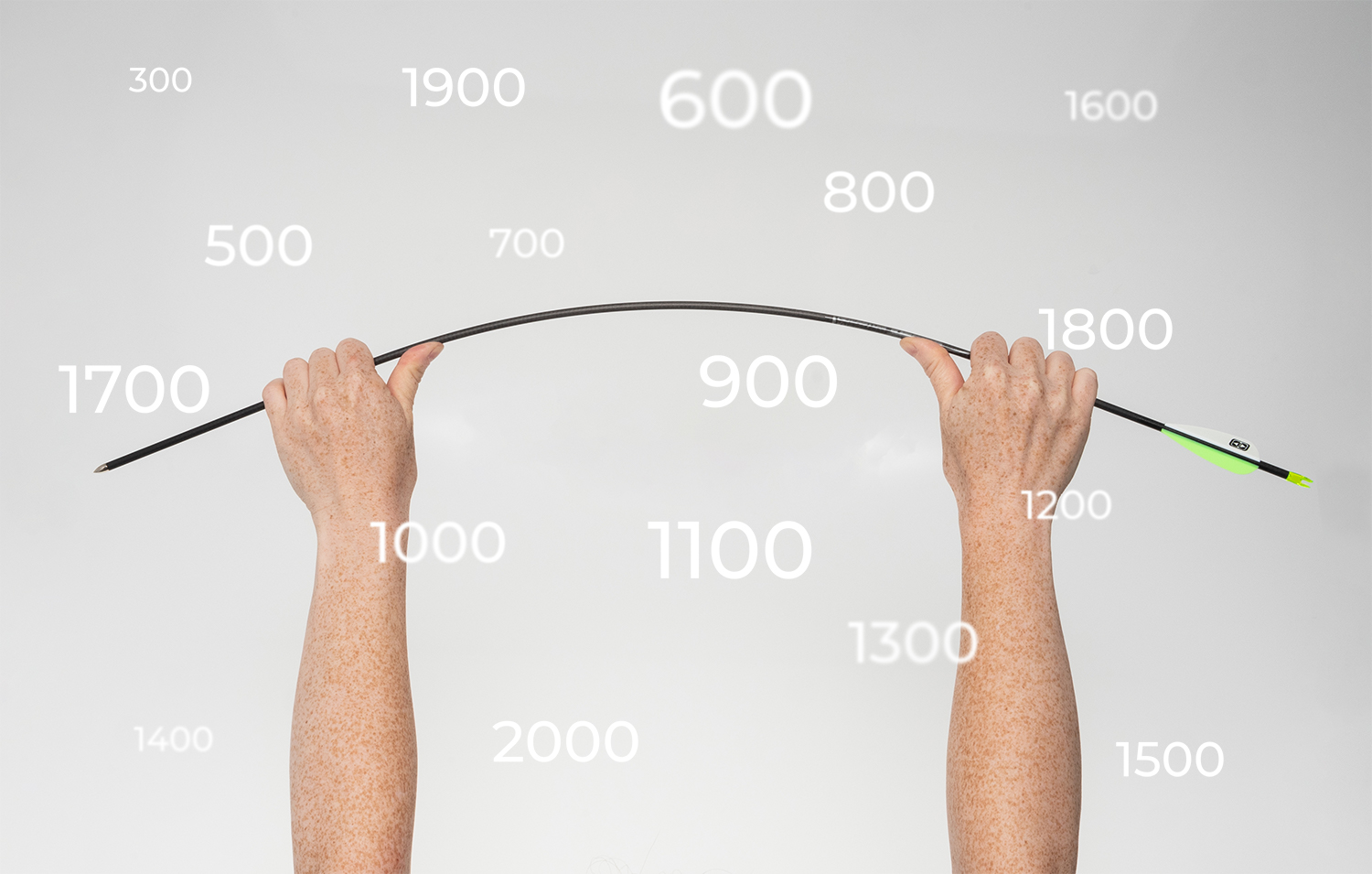

The term ’spine‘ (pronounced: ˈspaɪn) refers to its meaning as ‚backbone‘. You can imagine that quite well: Something with a strong spine is not easily bent. And the other way around: Something with little spine is quickly bent. The spine of an arrow is, in simplified terms, exactly that: the stiffness, or how easily the arrow can be bent.

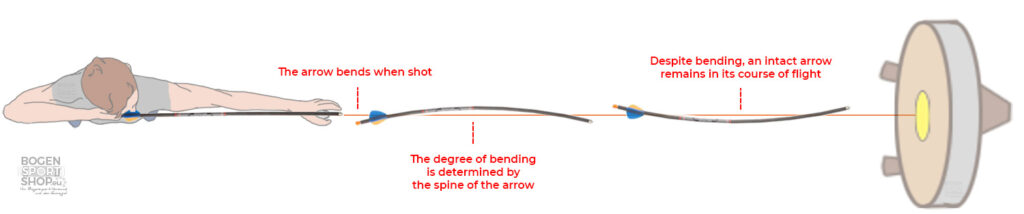

When you release the shot, force is applied to the arrow. The force causes the arrow to bend as it flies. The goal in choosing a spine is to match the deflection to the bow and the archer. A good tuning ensures an ideal flight and perfect score sheets.

This deflection of the arrow cannot be observed with the bare eye. But with a slow-motion camera, for example, you can probably see best that the arrow does not fly „straight as an arrow,“ but rather „wriggles“ into the target. In the Disney film Merida, for example, this phenomenon has been excellently observed and artistically realized.

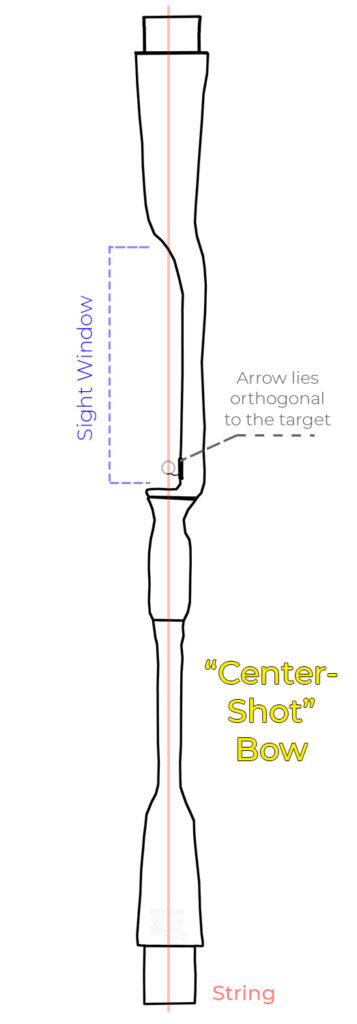

In primitive bows without a sight window, paradoxically (see also Archer’s Paradox), the arrow first has to wind its way around the grip (the starting position of the arrow is sideways to the target); here an accurate spine is very crucial for consistent results, because the arrow has to make ‚a bow‘ around the bow as correctly as possible.

We note: The strength of the bow causes the arrow to bend. The spine of the arrow specifies the degree of bending. The arrow must be neither too soft nor too hard, depending on the draw length and draw force. If the spine fits as far as possible, the arrow will remain in its shooting line even though it’s been bending.

How is the Spine Measured?

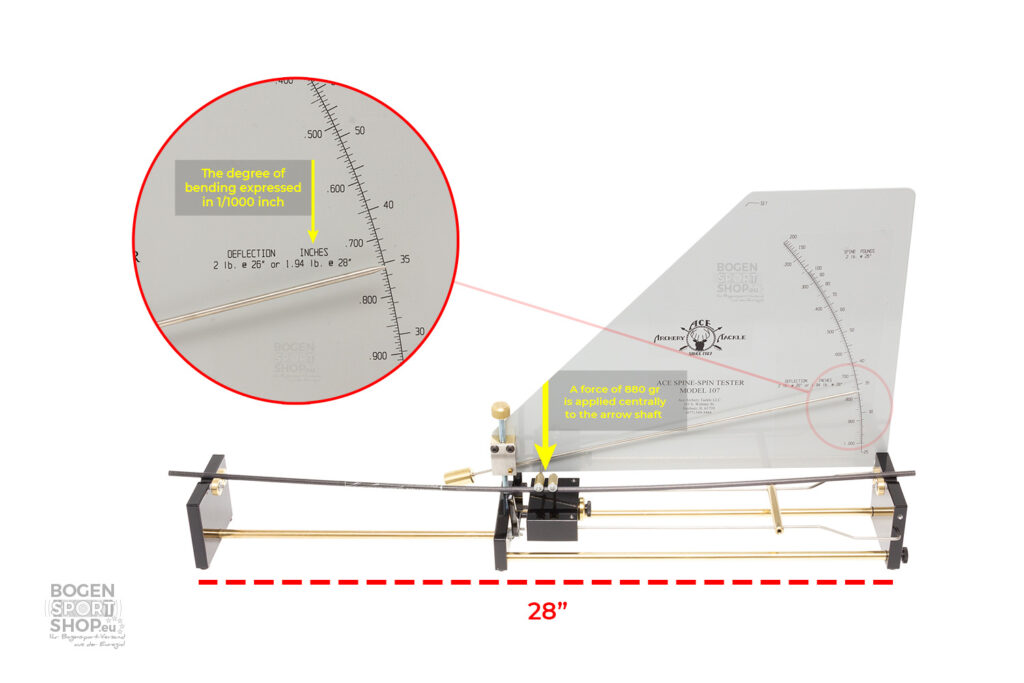

The method of measuring the spine is standardized today. The AMO (abbreviation for Archery Manufacturers Organization), a US manufacturer and dealer organization and the direct predecessor organization of the ATA (abbreviation for Archery Trade Association), published a booklet (AMO Standards) as early as February 1968 in which not only the measurement of the spine, but also all other standards applicable in archery, respectively archery construction – some of which are still canon today – are presented.

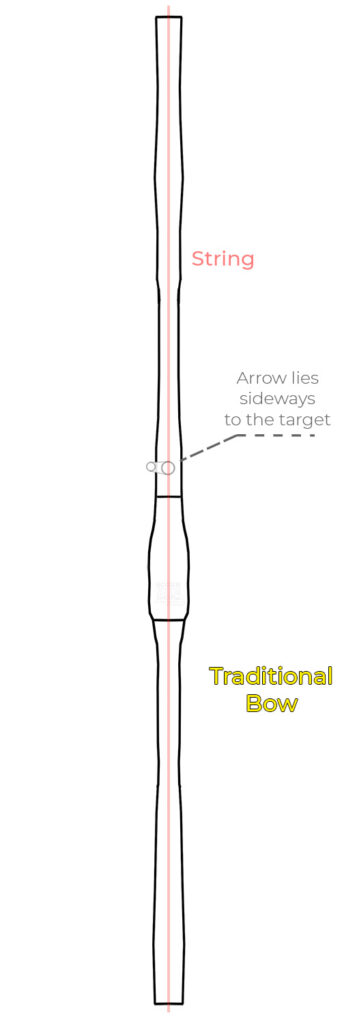

For the measurement of the spine, there are so-called spine testers (in our example, a model from ACE), where an bare arrow shaft is placed on two support points, which have a distance of 28″ from each other (according to the AMO standards, this distance is only 26″ for wooden arrows). A weight of 880 g is hung on the center of the arrow. Depending on how much the arrow deflects now reveals how soft, or hard the arrow is. This deflection is given in 1/1000 of an inch. A spine of 500 means that the arrow is deflected by 0.500 inch. 1200 would mean a deflection of 1,200 inches.

Intuitively, bows with higher draw weights should require stiffer arrows. It is probably less intuitive that these now have a smaller number printed on them. Conversely, weaker bows need a softer arrow, which is then marked with a higher number. Confusing!

I can already anticipate the question, „But I need 25 inch long arrows, what good is this measurement at 28 inches?“

This is important now! Do pay attention:

The length, of course, has a decisive influence on the stiffness of the entire component. In our case: the finished arrow. The longer the arrow, the more it bends under the same force. From this point of view, this can actually be understood without much technology or mathematics. Anyone who has ever extended a metal measuring tape just a few centimeters will have noticed how stiff and stable the material is. But if you pull it out 3 meters, it becomes a „soft noodle“. Or with hair. So does a long beard have different properties or is it made of a different material than, say, the short stubble of a 3-day beard? No – the length is only different but the hair is always the same!

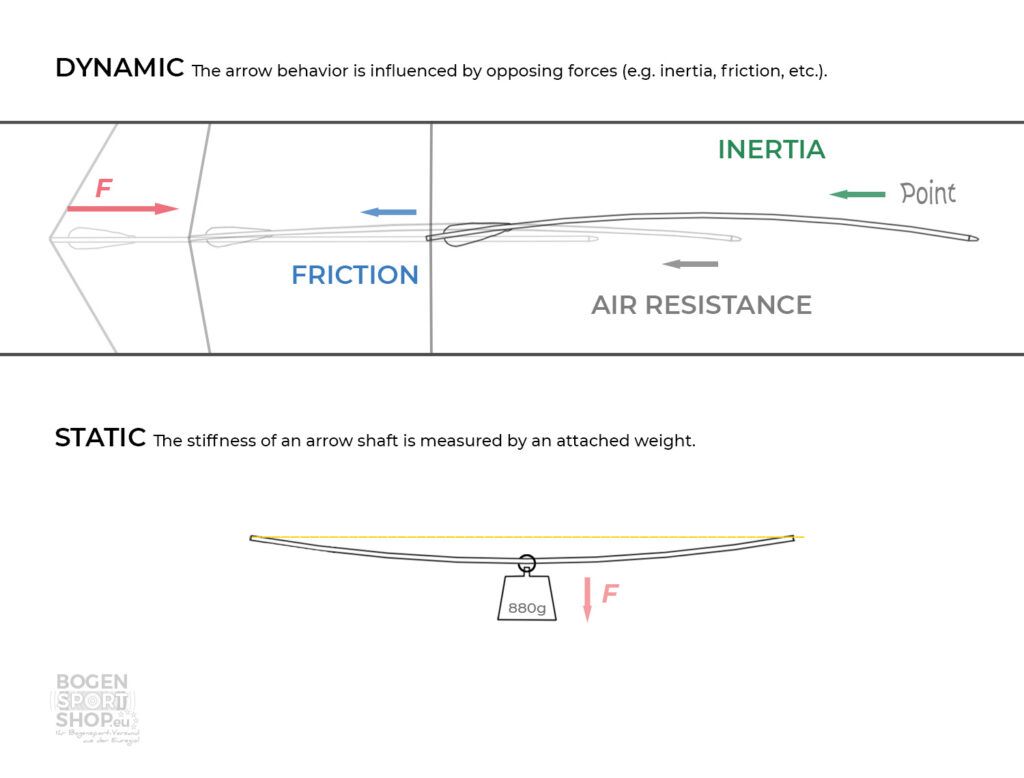

Static Spine vs. Dynamic Arrow Behavior

It is crucial to note that it makes a difference, of course, whether you hang a weight to the arrow’s centerpoint or press the force of the bow onto the arrow from behind. The static spine is only a tool – so to say -to find the right arrow shafts. But these must perform as well as possible when shot. And this best-possible „behavior“, depends not only on the stiffness of the shaft, but on the actual length of the arrow, as well as the weight of the tip or the launch speed of the bow. An arrow with a 120 gr point is softer than with 100 gr point. For example, a 60 lbs compound bow also shoots faster than a 60 lbs recurve bow. The reason why this is relevant: inertia.

The same reason we add weights to stabilizers: objects with greater mass are inert and cannot be set in motion as quickly. Let’s take a step back and think of a passenger car with an adult and a child in it in addition to the driver. For example, if this car accelerates abruptly after the traffic light turns green, the adult passenger would be pressed into his seat, but comparatively less than the child, and this is due to the weight.

In principle, such a force effect is also present in archery. If the string presses against the arrow from behind, thus moving the arrow forward, the point of the arrow is also affected, or more precisely, just as the passenger in the car presses against his seat, the point of the arrow presses against the shaft. Now, if there is a heavy point in front, for example, that is reluctant to be moved toward the target, an arrow would also deflect more than with a lighter point. The heavier the point or the faster the string, the more the arrow will deflect until it manages to accelerate the point to the same speed. So we are no longer looking at just an arrow lying statically on an apparatus, but we are looking at a system in motion.

Therefore, the term „dynamic spine“ is often used. However, confusion is almost pre-programmed, because it suggests a different, measured value, which is why we want to speak of „dynamic arrow behavior“ in this article. We would like to use the word „spine“ only for the value determined statically on the apparatus.

It is this dynamic arrow behavior that must fit the bow, the draw weight, and the archer. And the dynamic arrow behavior is the actual goal of spine tables like the following. In fact, you only get the static spine out of this, but this is also only to be seen as a means to an end, on the way to the ideal, dynamic arrow behavior:

Spine Table

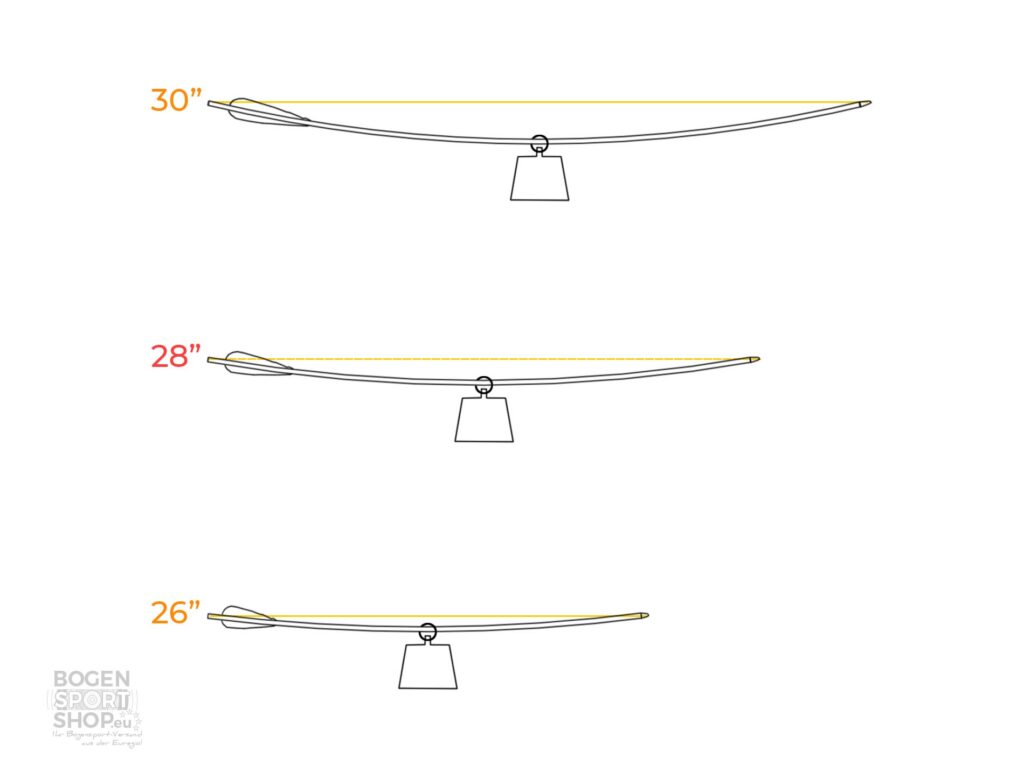

| Zuggewicht | 21″ | 22″ | 23″ | 24″ | 25″ | 26″ | 27″ | 28″ | 29″ | 30″ | 31″ | 32″ | 33″ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10-16 | 2000 | 2000 | 1900 | 1600 | 1400 | 1200 | 1100 | ||||||

| 17-23 | 2000 | 1900 | 1800 | 1500 | 1300 | 1100 | 1000 | 900 | 800 | 700 | 600 | 600 | 500 |

| 24-29 | 2000 | 1800 | 1500 | 1300 | 1100 | 1000 | 900 | 800 | 700 | 600 | 600 | 500 | 500 |

| 30-35 | 1800 | 1500 | 1300 | 1100 | 1000 | 900 | 800 | 700 | 600 | 600 | 500 | 500 | 400 |

| 36-40 | 1500 | 1300 | 1100 | 1000 | 900 | 800 | 700 | 600 | 600 | 500 | 500 | 400 | 400 |

| 41-45 | 1300 | 1100 | 1000 | 900 | 800 | 700 | 600 | 600 | 500 | 500 | 400 | 400 | 350 |

| 46-50 | 1100 | 1000 | 900 | 800 | 700 | 600 | 600 | 500 | 500 | 400 | 400 | 350 | 350 |

| 51-55 | 1000 | 900 | 800 | 700 | 600 | 600 | 500 | 500 | 400 | 400 | 350 | 350 | 300 |

| 56-60 | 900 | 800 | 700 | 600 | 600 | 500 | 500 | 400 | 400 | 350 | 350 | 300 | 300 |

| 61-65 | 800 | 700 | 600 | 600 | 500 | 500 | 400 | 400 | 350 | 350 | 300 | 300 | |

| 66-70 | 700 | 600 | 600 | 500 | 500 | 400 | 400 | 350 | 350 | 300 | 300 | ||

| 71-76 | 600 | 600 | 500 | 500 | 400 | 400 | 350 | 350 | 300 | 300 |

If we specify our draw weight, the draw length, possibly even the point weight to search in such a table, then these are all parameters that influence the dynamic arrow behavior. The result is a static spine that helps us find the right shelf of arrow shafts. The static spine as a numerical number is therefore not in itself the decisive factor and is good for nothing more than a fixed reference unit for orientation. If you cut the shafts to the desired length and glue the tip, the arrow should behave as you want it to.

Whether the arrow then really fits optimally can then be found out with various shooting tests (e.g. paper test, bare shaft test, etc.). If you see after these tests that there is still some need for optimization, the purchased arrow with the corresponding spine can of course no longer be changed. But there are still small ways to improve the arrow. For a clean arrow flight, the draw weight and point weight can still be modified, and the length of the arrow could still be adjusted, though just by a small amount. However, such optimizations really belong to the field of fine tuning and are usually carried out by experienced (competitive) archers with a well-tuned bow setup.

So, can you put a number on this dynamic behavior? You could try, but there isn’t a system out there for that. And frankly, you don’t even need to. This is why we do not want to talk about „dynamic spine“ and certainly not about a „dynamic spine value“. There is only one spine, and that one is written on the arrow shaft.

Nice article, but the example with car accelerating and a pressure on adult vs child is wrong. They will experience the same acceleration and heavier person will feel more significant force than lighter.

I think this analogy is difficult in general, because as you say, the acceleration is independent of the mass. You could even argue that the acceleration doesn’t really feel different. The force might be higher for an adult, but the adult also has a greater contact area on the seat.